Jan 26, 2026

Introduction

What AI agents are, why businesses are investing, and why architecture matters

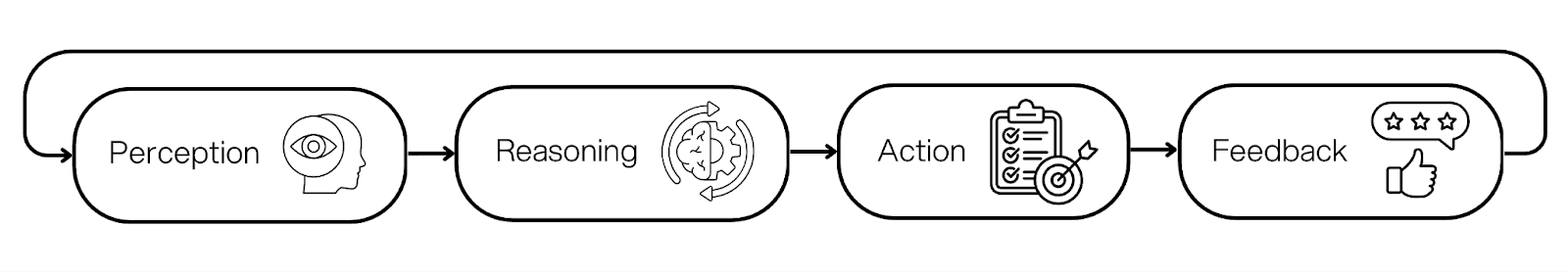

An agentic workflow is a system that can take a goal and work through steps to get an outcome. It can decide what to do next, call tools that connect to real systems, check what happened, and then continue.

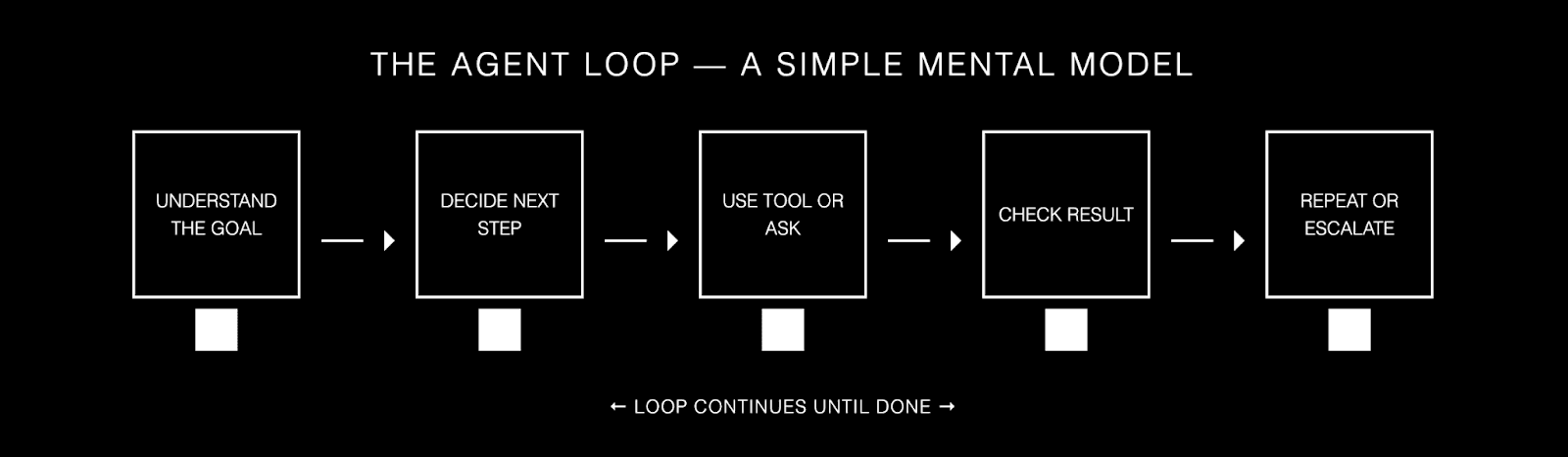

If you want a simple mental model, think of an agent as a loop.

Understand the goal. Decide the next step. Use a tool or ask a question. Check the result. Repeat until done, or escalate.

The business case

Why do organizations care? Because a lot of work in the real world is not one step. It is: look something up, cross check it, apply a policy, fill a template, trigger an action, and capture what happened.

Traditional automation struggles when inputs are messy, when the path is not fixed, or when exceptions are common. Agents handle those situations better because they can choose steps, not just follow a script.

Agents are being used in customer support, security and IT operations, internal knowledge work, and document heavy processes. Public case studies talk about outcomes like higher resolution rates in support, big time savings in security workflows, and faster turnaround on complex internal documents such as credit risk memos and decision packs.

It is worth being honest here: agents do not replace a whole function overnight. They remove the repetitive parts, handle the first pass, and reduce back and forth. That is often where the measurable value sits.

Why architecture is the make-or-break factor

Here is the part that matters: these wins do not come from 'making the model smarter'. They come from choosing the right architecture and the right guardrails for the use case.

Architecture is how you decide what the agents you choose for your workflow can do, how much freedom they have, and how they behave when something goes wrong.

In 2026, architecture matters even more for two reasons. Tool access is getting easier through standard connectors, and models are better at taking actions across many steps. Both are great, and both raise the cost of mistakes.

So the core idea of this guide is simple: match the architecture to the business case. Give the system the smallest amount of freedom that still delivers the outcome. Then put your effort into tool design, safety, and observability.

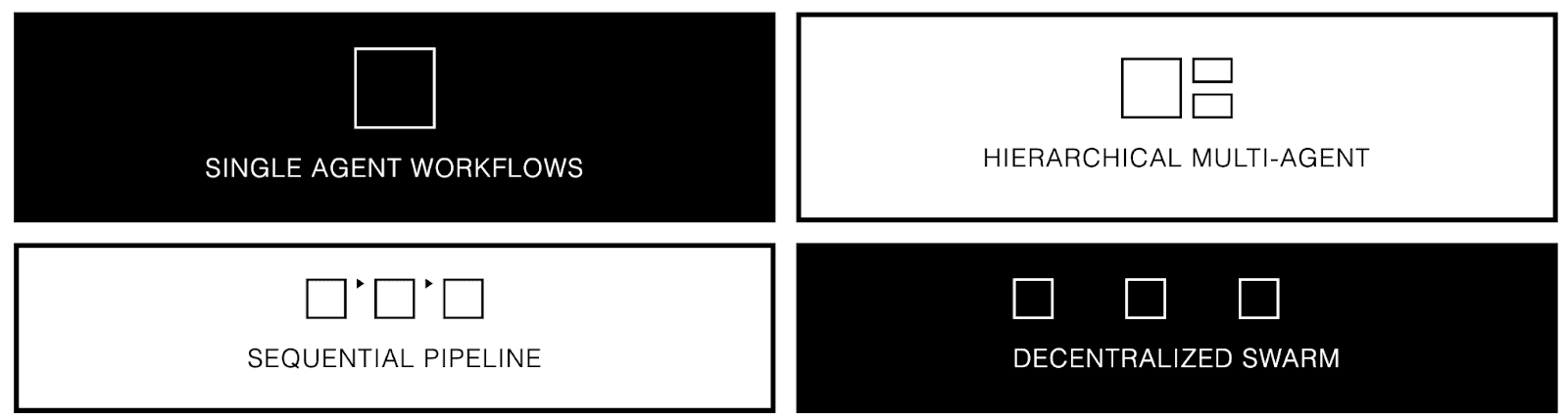

A workflow-oriented taxonomy that stays useful

A lot of articles classify architectures by features like retrieval, memory, or tool use. Those features matter, but they are not the core structure. A single agent can use tools, retrieval, and memory. A multi agent system can do the same, with different agents having the same access or different access. For an internal taxonomy, it is often more practical to classify systems by workflow shape and control topology. This guide uses four categories: single agent workflows, hierarchical multi agent workflows, sequential pipeline workflows, and decentralized swarm workflows. Everything else is a capability you can add to any of them.

And in more complex systems, you should expect to combine patterns. In practice, many production setups are custom workflows that mix these types, for example a sequential pipeline that includes a hierarchical “supervisor and workers” step in the middle, or a single agent that routes specific sub tasks into a small specialist swarm for cross checking. The categories still help, because they give you a clear starting point and a shared language, even when the final system ends up being a hybrid.

After this introduction you will find a comparison table, then a tour of the four architectures. For each one, I will give you a definition, what it looks like, when to use it, when not to use it, and a short example. Then we will cover agent design best practices and what is next.

Comparison: Four workflow-oriented architecture types

Use this table to shortlist the right workflow shape. The rest of the guide explains how each type behaves in real systems, and how capabilities like tools, retrieval, memory, and human approval can be layered into any of them.

Architecture type | Control topology | Execution flow | Best for | Main risk | A sensible starting setup |

Single agent workflow | One agent owns decisions | Emergent within one loop | Simple to medium tasks, fast iteration | Drift and looping without guardrails | 1 agent + strict tools + stop conditions |

Hierarchical multi agent workflow | Manager delegates to workers | Mix of parallel and sequential | Complex tasks that split into parts | Coordination overhead and hidden cost | Supervisor + 3 to 8 workers + shared state |

Sequential pipeline workflow | Fixed chain of agents | Step A → Step B → Step C | Repeatable processes with a known path | Brittleness on edge cases | Pipeline steps + validation + fallback route |

Decentralised swarm workflow | Peer agents coordinate | Emergent, message driven | Exploration, debate, broad coverage | Hard to predict and hard to debug | Shared memory or bus + role rules + time limits |

Agentic workflows architectures

All four types can use the same building blocks: tools, retrieval, memory, and human approval. The difference is how control is organized and how work flows through the system.

Pro tip: Start simple. In most teams, the first working version is a single agent. You add multi-agent structure when you have a clear reason: you need parallelism, you need separation of duties, you need better reliability, or you need tighter permission boundaries.

How to choose in five questions

When teams struggle, it is usually because they picked an architecture that gave too much freedom for the risk level, or too little flexibility for the real world messiness. These five questions get you to a good first choice.

Do you already know the steps, or does the system need to figure them out?

How risky is a mistake: small annoyance, or real financial, legal, or customer harm?

How many systems does the agent need to touch, and can it use APIs or does it need to operate a UI?

Will the task finish in one sitting, or does it need to run for minutes or hours with checkpoints?

Do you need one capability, or many different capabilities under one product umbrella?

Now, let’s talk about the main four architectures.

1) Single agent workflows

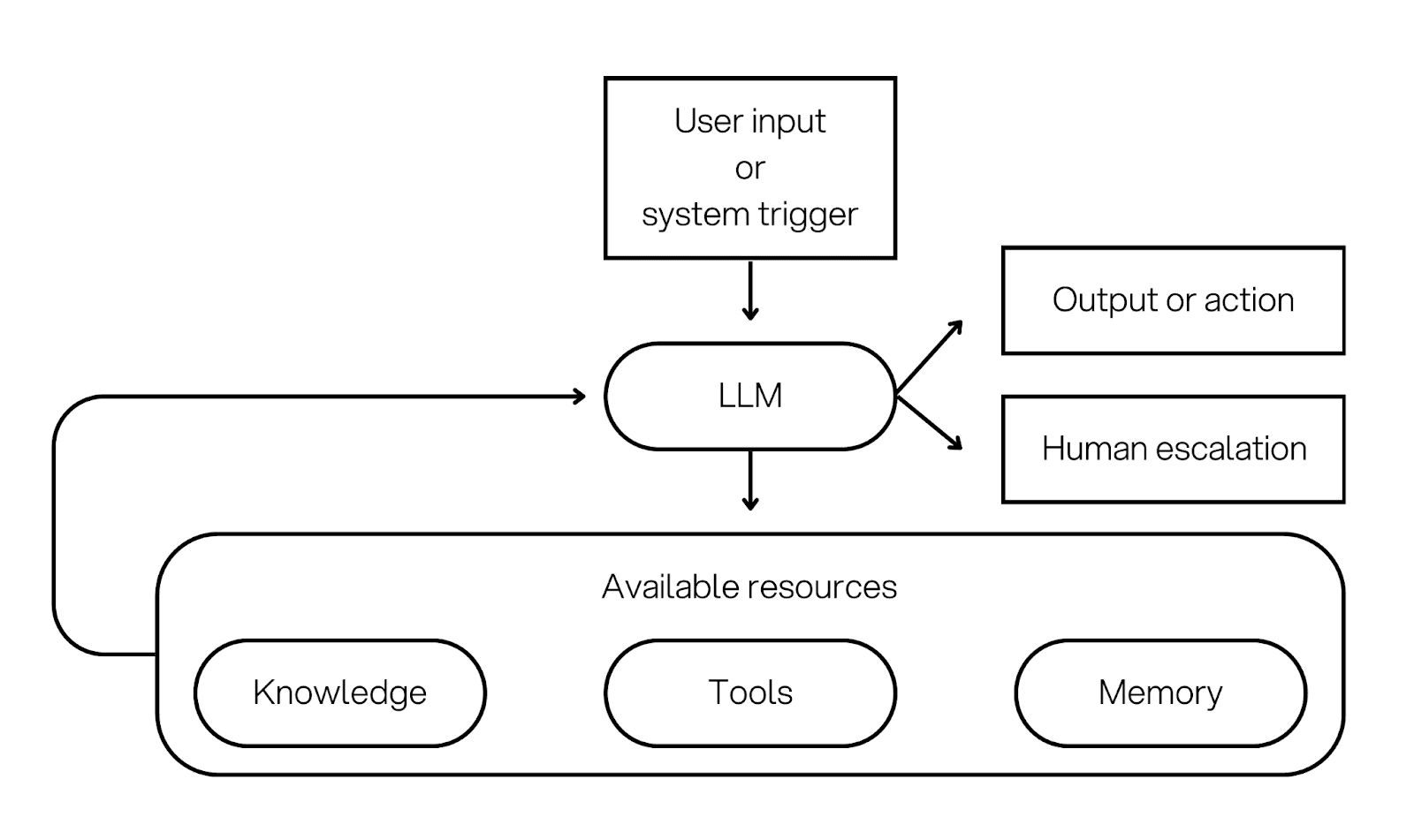

Definition: One agent handles perception, planning, tool use, and action end to end.

Architecture overview: The agent runs a loop. It reads the goal, picks a next step, and uses the resource layer to act. The loop continues until the agent finishes, asks a clarification question, or escalates.

A key point: a single agent can still be 'full stack'. It can use tools, retrieval (RAG) for grounded answers, and memory for continuity. You can also add human approval gates for risky actions.

When to use it: Use this when you want speed and you have a small resource set. It is also a strong fit for tasks that are naturally linear, do not need parallel work and where the tasks is well-defined.

When not to use it: Avoid this when the task is long running, when you need strict separation of duties, or when mistakes are expensive. In those cases, you often want structure that a single loop does not give you.

Example: A support assistant that retrieves relevant policy text and recent account history, uses tools to pull order details, drafts a response with source citations, and asks for approval before sending if the message is high impact.

How it extends to multi agent architectures: When the single agent starts to feel overloaded, you usually add structure in one of three ways. You add a supervisor that delegates. You split the work into a pipeline. Or you allow several peer agents to coordinate. Those are the next three categories.

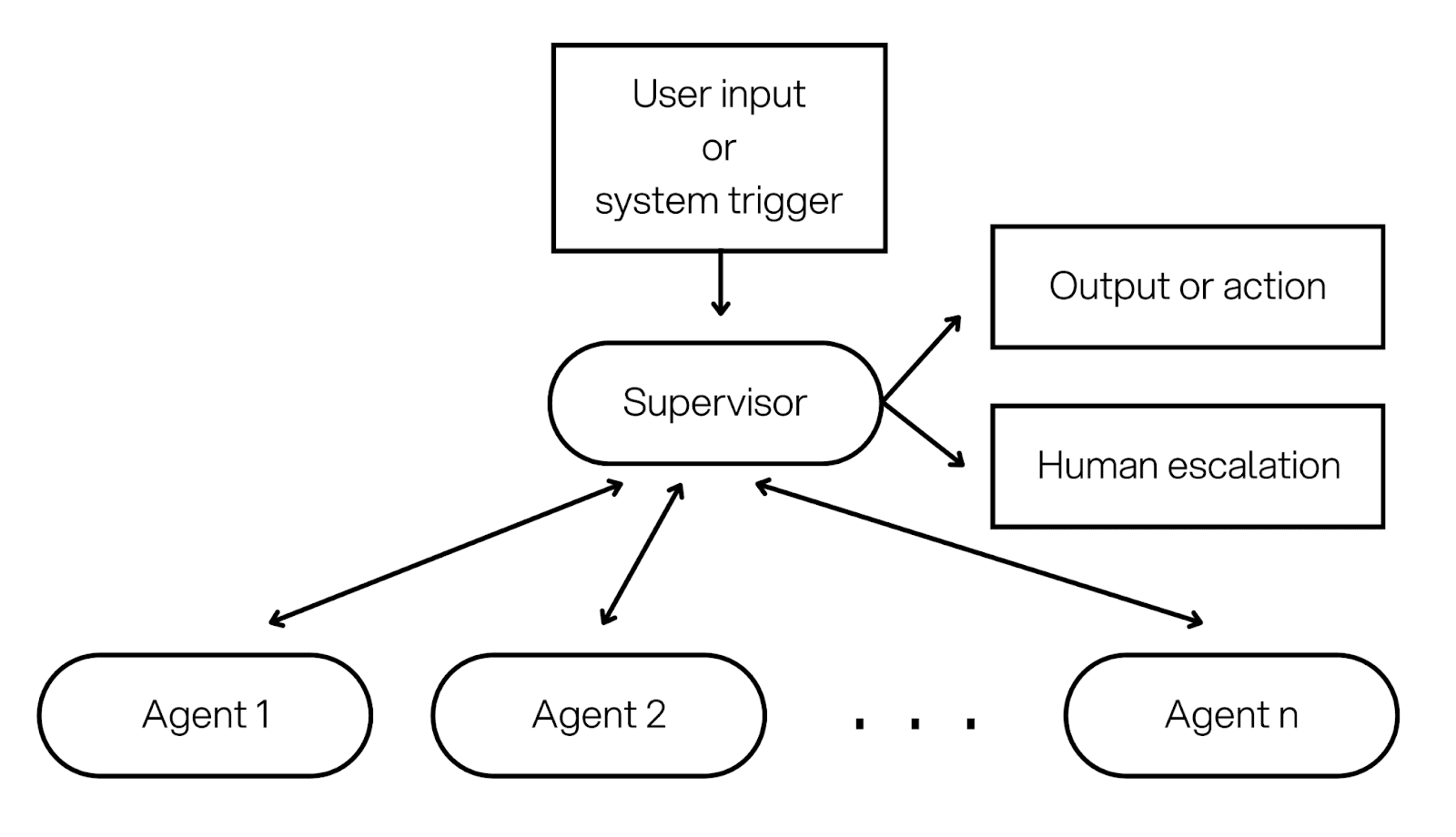

2) Hierarchical multi agent workflows

Definition: A supervisor agent breaks down work and delegates to specialist agents, sometimes in multiple layers.

Architecture overview: A supervisor holds the goal and decides what sub tasks are needed. Each worker agent runs with a narrower role, a smaller tool set, and clearer permissions. The supervisor collects results and produces the final output or action plan.

This architecture is also used where organizations often put separation of duties. For example, one agent can retrieve documents, another can run calculations, another can draft, and a final approver step can be human.

When to use it: Use this when the task naturally splits into parts, when parallel work saves time, or when you need different permission boundaries. It is common in research plus writing, audits, comparisons, and report generation.

When not to use it: Avoid this when the task is small. More agents mean more cost and more operational work. Also avoid it if you cannot trace decisions, because coordination problems will hide inside the handoffs.

Example: A market analysis system where a supervisor delegates to three workers: one pulls competitor data from tools, one retrieves internal notes via RAG, one summarises customer feedback. The supervisor merges the evidence into a memo and requests human approval before publishing.

3) Sequential pipeline workflows

Definition: A fixed chain of agents or steps where the output of step A feeds step B, then step C, with minimal branching.

Architecture overview: This looks like an assembly line. Each step has a clear contract. Step A extracts, Step B validates, Step C drafts, Step D submits. You can implement steps as agents with narrow roles, or as simple LLM calls in code. The orchestration is mostly static.

Pipelines are usually the easiest to test. You can measure each step, add hard checks, and keep cost predictable. Human escalation or validation can be implemented at any stage of the pipeline.

When to use it: Use this when the process is known and repeatable, such as onboarding, compliance checks, document processing, ticket enrichment, or generating a standard decision pack.

When not to use it: Avoid this when the process is full of exceptions, or when user intent changes often. Pipelines get brittle when you keep patching special cases.

Example: A vendor onboarding pipeline: Step 1 extracts fields from documents, Step 2 checks completeness and flags missing items, Step 3 drafts a summary for review, Step 4 creates the record in the internal system. If validation fails, it routes to a human review lane.

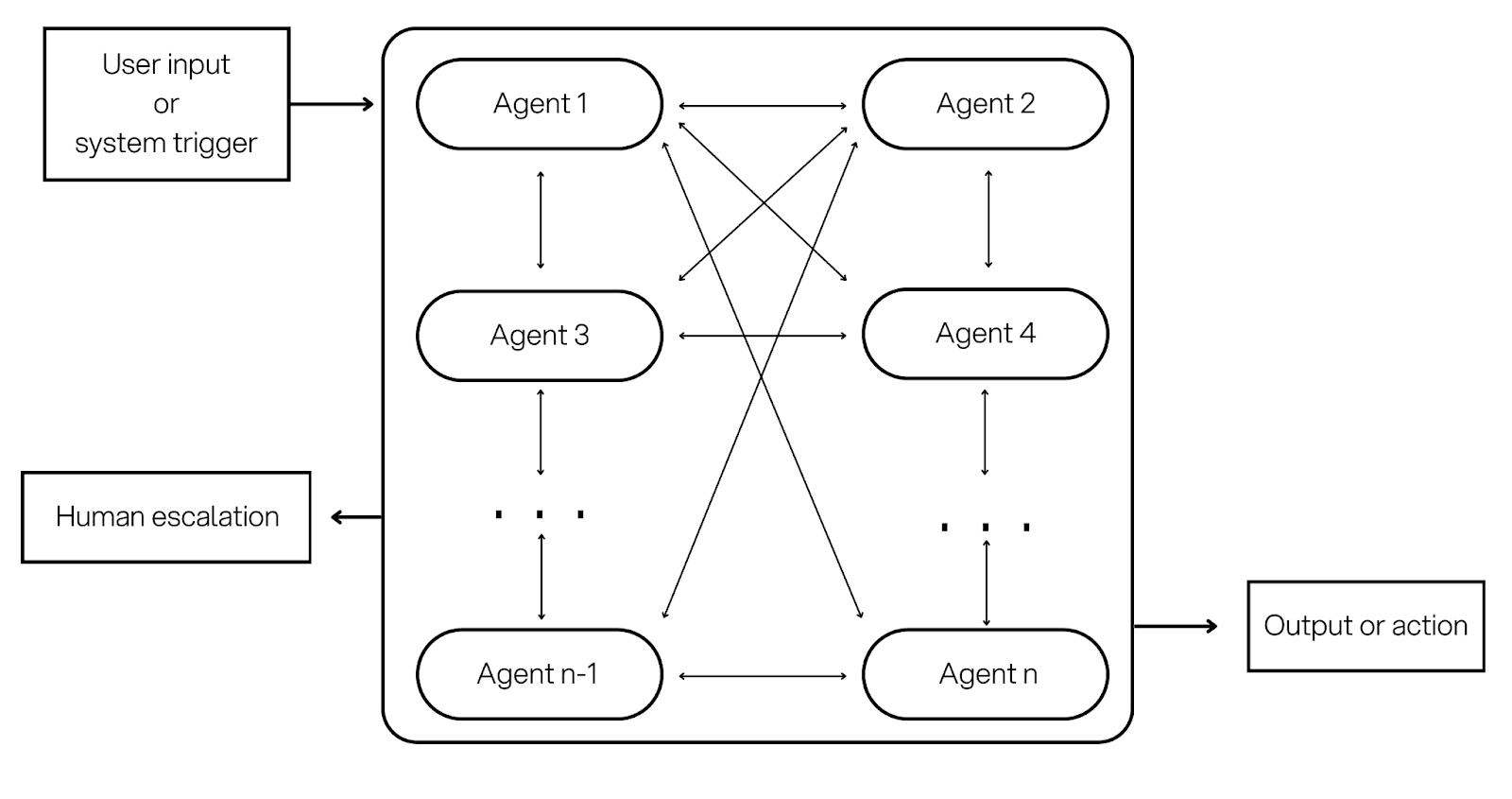

4) Decentralized swarm workflows

Definition: Multiple peer agents coordinate through shared memory or messaging, with no single permanent controller.

Architecture overview: Instead of one supervisor agent, you have peers with roles. They share information through a memory store or messages. Coordination is emergent: agents propose ideas, challenge each other, and converge on a result through rules and time limits.

This pattern can produce broad coverage and creative problem solving. It can also be harder to predict and harder to debug, so it needs strong constraints and tracing.

When to use it: Use this for exploration, brainstorming, debate style analysis, or situations where you want multiple independent perspectives before deciding. It can also help when you want redundancy, such as cross checking a plan from different angles.

When not to use it: Avoid this for safety critical action taking, or when you need predictable behaviour. Without strict limits, swarms can loop or amplify errors.

Example: A risk review swarm where three agents independently assess a proposal, each from a different lens (policy compliance, financial risk, operational risk). They share notes in a shared memory store, then a final synthesis step produces a structured recommendation with cited evidence.

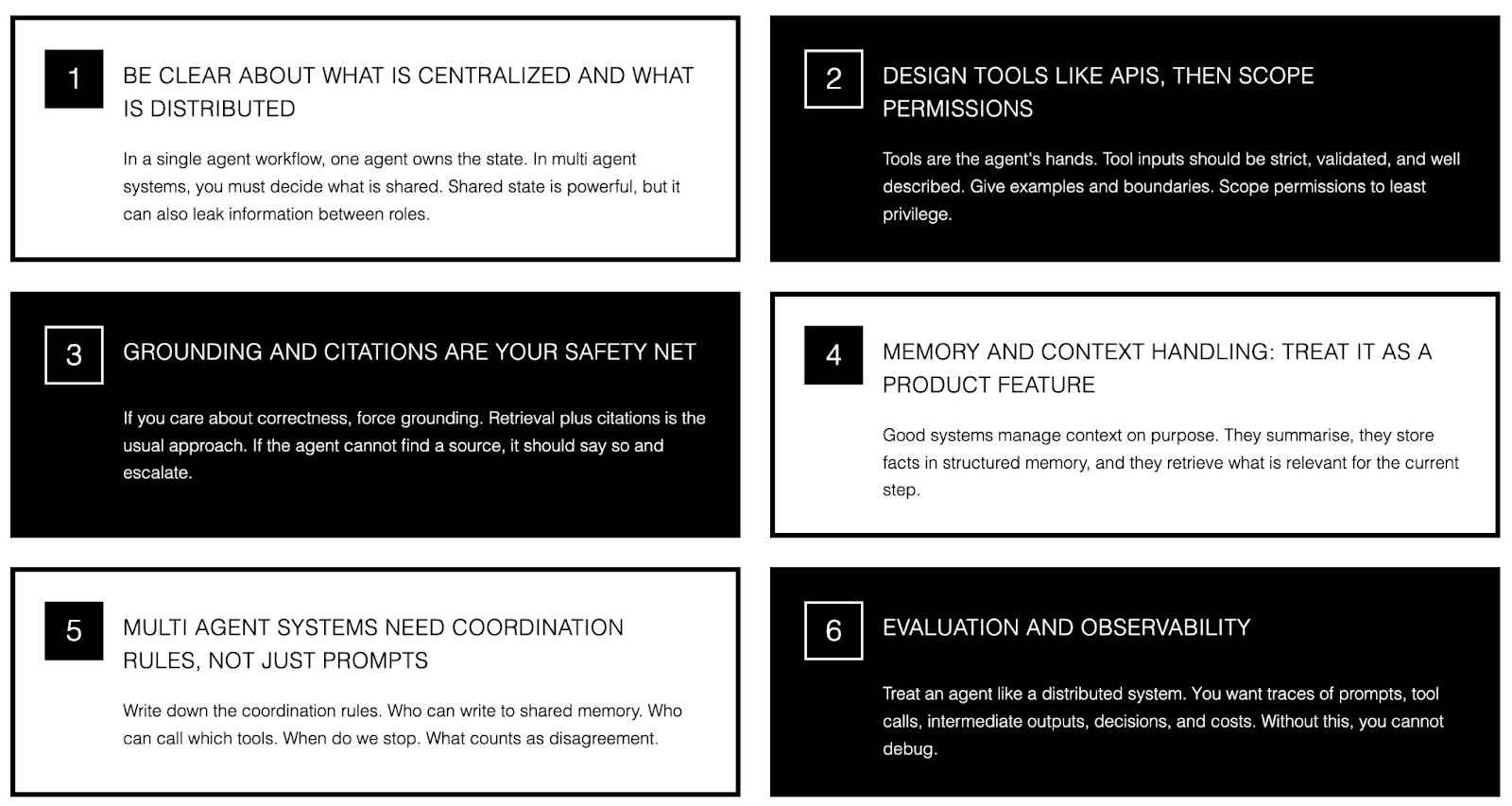

Agent design best practices

These practices apply across all four architectures. The shape of the workflow changes, but the production problems are very similar: tool safety, data grounding, state management, evaluation, and operations.

Be clear about what is centralized and what is distributed

In a single agent workflow, one agent owns the state. In multi agent systems, you must decide what is shared. Shared state is powerful, but it can also leak information between roles. A good default is: share only what is needed, and keep sensitive fields scoped to the agent that needs them.

Design tools like APIs, then scope permissions

Tools are the agent’s hands. Tool inputs should be strict, validated, and well described. Give examples and boundaries, including what not to do. Then scope permissions to least privilege. Give read access before write access. Separate environments. Require explicit consent for sensitive actions.

Grounding and citations are your safety net

If you care about correctness, force grounding. Retrieval plus citations is the usual approach. If the agent cannot find a source, it should say so and escalate. This matters for single agent systems and multi agent systems. It is easy for a swarm or supervisor to turn 'a guess' into a confident final output unless you make evidence a requirement.

Memory and context handling: treat it as a product feature

Longer context windows are making it easier to carry more information in one run, but it is still risky to just keep appending. Good systems manage context on purpose. They summarize, they store facts in structured memory, and they retrieve what is relevant for the current step.

A simple rule: use short term memory for the current job. Use long term memory only for stable facts that you can edit and audit. Avoid storing sensitive details unless you have a clear business reason and consent.

Multi agent systems need coordination rules, not just prompts

If you use hierarchical or swarm setups, write down the coordination rules. Who can write to shared memory. Who can call which tools. When do we stop. What counts as disagreement. When do we escalate. Without these rules, most failures look like 'the model was random' when the real issue was coordination.

Evaluation and observability

Treat an agent like a distributed system. You want traces of prompts, tool calls, intermediate outputs, decisions, and costs. Without this, you cannot debug, you cannot do meaningful evaluation, and you cannot prove what happened if something goes wrong. For multi agent systems, you also want to see the handoffs: who said what, and what state they read.

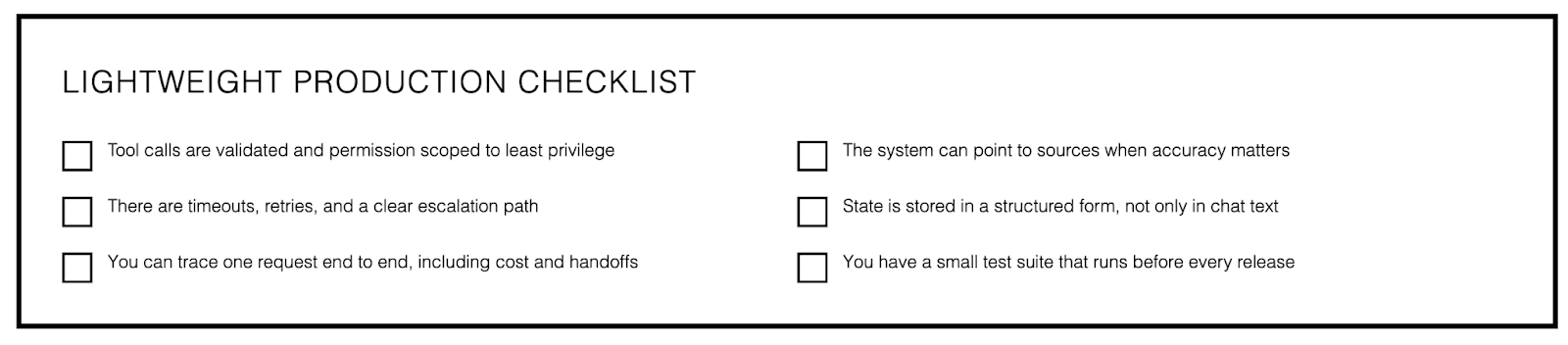

A lightweight production checklist

Tool calls are validated and permission scoped to least privilege.

The system can point to sources when accuracy matters.

There are timeouts, retries, and a clear escalation path.

State is stored in a structured form, not only in chat text.

You can trace one request end to end, including cost and handoffs.

You have a small test suite that runs before every release.

What's next for AI agents

The trend line is clear: agents will be able to do more, with less custom glue code. The cost is that safety and governance become part of the core system.

Standardized tool connectivity is the biggest shift. Protocols such as the Model Context Protocol aim to remove the need for bespoke connectors. You get faster integrations, reusable tool servers, and clearer schemas. You also get a bigger attack surface, because every tool is a capability.

Longer context windows are also changing what is feasible, but they do not remove the need for good context management. Teams will get better results by combining longer context with retrieval, summarization, and structured memory, rather than dumping everything into the prompt.

We are also seeing more action taking agents that can operate software interfaces, not only APIs. This helps in organizations with legacy systems. It also raises the risk of unintended actions, so sandboxing, approval gates, and strong audit logs become more common.

Runtimes and orchestration layers are maturing too. Checkpointing, tracing, and policy enforcement are becoming standard building blocks. The direction is to make agents behave more like dependable software, even as the model does more of the reasoning.

Over time, architecture can get simpler because models are improving at tool discovery and tool use. The aim is not to keep stacking more agents. The aim is to keep the system clean, and let the model do more reasoning while your architecture controls safety, cost, and reliability.

How to stay ready without overbuilding

If you want a practical rule: invest in foundations that survive model changes. Clean tool boundaries. Clear permissions. Strong traces. A small evaluation set. Those pieces keep paying off as models improve, and they make upgrades less scary.

Standardize tool schemas and permission boundaries early.

Keep traces and structured state so you can compare behavior across model versions.

Treat evaluation as continuous, not as a one off before launch.

Add autonomy in layers: single agent first, then hierarchical or pipeline, then swarm if you truly need it.

Final thoughts

AI agents are now a real operational lever. They can reduce manual back and forth, remove busywork, and help teams move faster without losing quality. But the win comes from matching architecture to the use case, not from chasing maximum autonomy.

Start with clarity on the outcome you want. Pick the simplest workflow shape that can achieve it safely. Then put your effort into tool design, grounding, explicit state, and observability. That is what makes agents dependable in 2026.